On my Bookshelf | Dmitry Markov – Russia² (Россия²)

On my Bookshelf

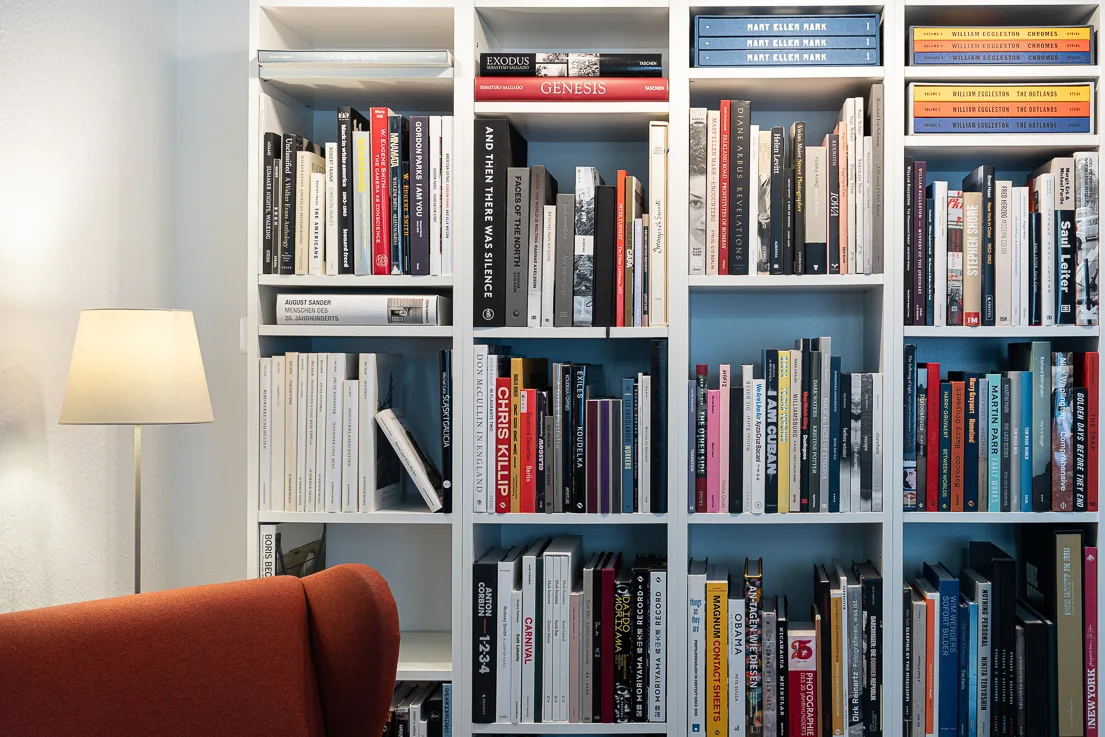

In this column, I occasionally present a photo book that is close to my heart. It is not – or not necessarily – a new publication. It is simply a book that somehow fell into my hands and that I would like to recommend to others. And yes – of course it’s on my bookshelf.

It’s a bit of a continuation of my Photo book of the month column – just not necessarily as regular as before. And I’ve generally made the column a bit shorter and tighter. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

Prologue

By the end of 2025, Russia’s brutal war of aggression against Ukraine will have dragged on for nearly four years. It offers little reason for hope—neither for the world, nor, above all, for the Ukrainian people. Russia has increasingly become a pariah on the international stage, and Russian citizens have, to some extent, been held collectively responsible. There is some truth in this reaction, though certainly not in every case. The consequences have spilled into many spheres, including culture. Russian artists, too, have largely disappeared from our everyday cultural landscape.

As this year draws to a close, I’d like to push back against that perceived taboo and introduce a book by the Russian photographer Dmitry Markov.

Yet none of the points above is the main reason I’m highlighting this book now. This time, alongside looking at Markov’s work from an artistic perspective, I also want to explore something of the “technical side” behind it. More on that in a moment…

About the Photographer | Dmitry Markov

Life and career

Dmitry Alexandrovich Markov, to give him his full name, was a Russian journalist and photographer. Born in Pushkino in the Moscow Oblast in 1982, he initially studied at an engineering college. Even then, however, he was already immersed in photography and, by his own account, went on to study under the Russian photographer Alexander Lapin.

Markov dedicated his work to capturing the lives of those on the margins of society—documenting the struggles and small triumphs of homeless people, drug addicts, orphans, and residents of remote rural communities. His images reveal the stark realities of these often overlooked worlds with both unflinching honesty and deep empathy.

According to Wikipedia, this commitment eventually led him to move from the Moscow region to Porkhov in the north-western Russian oblast of Pskov. By that time, Markov was already struggling with drug addiction. After a period of recovery, he began working with orphans from reformatories through the public organisation Rostok in Pskov in 2007, a role he kept until 2012. He also served as a caregiver in the children’s village of Fedkovo.

Together with staff from various charitable organisations, he visited numerous social institutions—from orphanages to penal colonies. During these visits he photographed the lives of the young people he encountered and documented their stories on his blog. By his own account, these experiences left a deep mark on him—at times even pushing him to the edge of his sanity.

Development of his photographic style

Markov’s participation in David Alan Harvey’s Burn Diary project in 2013 set him on the path to wider recognition. He adopted the project’s core principles for his own Instagram profile—shooting exclusively with a mobile phone and posting only images taken on the same day.

These daily Instagram photographs later became the foundation for several exhibitions as well as for his published books. His work earned significant acclaim, and in 2015 he became one of only three photographers worldwide—and the first Russian photographer ever—to receive a grant from Getty Images, one of the world’s major photographic agencies.

Political activity

Markov also began photographing Russian street protests in 2012. Many years later, on 2 February 2021, police arrested him near the Moscow City Court, where he had gone to show support for Putin’s opponent Alexei Navalny, who was then in custody. Officers took him to the Kosino-Ukhtomsky police station, where he captured a striking image: a security guard in a bulletproof vest and balaclava seated beneath a portrait of President Vladimir Putin.

The photograph quickly went viral, and people soon regarded it as one of the most recognisable visual symbols of Putin’s increasingly autocratic rule. Later, an auction sold a signed print for 2 million roubles and donated the proceeds to two organisations that support people detained during political protests.

Sadly, Dmitry Markov died on 15 February 2024 at the far too young age of 41 from a methadone overdose. He had battled addiction for decades, had eventually contracted HIV, and in the end was clearly exhausted and overwhelmed by the weight of these struggles.

About the Photo Book | Russia² (Россия²)

Markov’s third book, Russia², was published in 2022—its title almost certainly intended to be read as “Russia Square,” a nod to the square format of the photographs showcased throughout. Alongside Russia², he also released #Draft(#Chernovik) in 2018 and Cut Off in 2019. I’m not familiar with the latter, which appeared only in a very limited print run and was packaged together with an LP of the same name. I do, however, own his first book, and can highly recommend it.

Russia² continues Markov’s tradition of social documentary photography, capturing everyday life—above all in the Russian provinces. To me, the book follows no obvious structure or chronology, which makes perfect sense given the core principle of his work mentioned earlier. Each of the 171 photographs across the book’s 208 pages could easily stand on its own and tell a complete story. Yet together they form a tapestry of countless narratives about Russia—not only as Markov observed it, but as he lived it.

Treemedia published Russia² in 2022. You can probably still find the first edition, and reprints—like my own copy, apparently from 2025—are also fairly easy to track down online.

Why is it so important?

I hardly know where to begin.

Perhaps the best place is with the tool he used. As I hinted at in the prologue, this is remarkable in its own right. Since 2013, Dmitry Markov photographed exclusively with a smartphone. As much as I love traditional cameras—and as much as they form part of my own passion for photography—it becomes clear in his case that sometimes the equipment simply doesn’t matter. I very much doubt that a “real” camera would have improved his work in any meaningful way.

About his motivation

As a great admirer of documentary photography, I am naturally drawn to Dmitry Markov’s work. His images are direct and unguarded, brutal yet tender, haunting yet gentle. And they are never “stolen.” By this I don’t only mean the portraits in which the subjects clearly posed. I also mean the everyday scenes of individuals or groups of people. Markov never hid what he was doing; he was often right in the middle of things, fully visible and fully present. He was genuinely one of them—the very people of Russia whose lives he photographed.

People often accused him of defaming his homeland—of portraying Russia in a bleak light and showing only its “ugly face.” Such criticism was especially common among Russian nationalists. Markov, however, rejected these claims entirely. On the contrary, he insisted that he simply photographed the reality he saw and the reality he knew.

Viewers see some of my subjects as bleak, if not, let’s be honest, depressing. But I feel the opposite: peace.

Dmitry Markov

He was also familiar with the opposite side of Russian life—the lavish parties of Moscow’s millionaires, which he occasionally photographed simply to earn a living. But those images held no real meaning for him, unlike the photographs of people whose lives and struggles he genuinely understood.

Others have interpreted his work very differently—seeing in it artistic depth, human insight, and an unvarnished truth. Some even place him in the tradition of Russian poets, describing him as a kind of photographic Dostoyevsky, or—through more Western eyes—as a Russian Henri Cartier-Bresson. It will come as no surprise that I find myself aligned with these admirers, and with Markov’s own view of his work.

His photography is an exercise in true presence and humanity. It is not driven by pity, but by solidarity, recognition, and—above all—respect.

About his inner pain

That Dmitry Markov struggled—both with the country he deeply loved and with his own life—will come as no surprise here. I have already touched on this in the brief outline of his biography and work.

He seemed torn between his social commitment, his profound affection for his homeland and its people, and the despair and hopelessness that increasingly overtook him, especially in the final years of his life. What strikes me as all the more remarkable is that this darkness is not—at least not often—visible in his photographs. They are not relentlessly bleak, yet they make no attempt to soften or romanticise reality.

For those close to him, it had become clear by the early 2020s that he could not continue on as he had. And so, sadly, Russia² stands as the final printed work of a photographer who, to me, was truly remarkable. The last image on his Instagram account, posted on 6 February 2024, is all the more poignant in this light. It can—indeed, it must—be read as a reflection of his fragile mental state at the time.

One day, the happy moment will come along when, at last, I’ll die. My few neurons will stop firing, and, along with them, all the mistakes that have piled up over the course of my tormented existence will dissipate. But, when all the dross is forgotten, my photos will remain. That’s the part of me for which I feel no shame, and which can be thrown into the future as little paper planes.

Dmitry Markov

Even though I am ending with a quote from Dmitry Markov that may seem unbearably sad at first glance, I want to draw attention especially to the final lines. For they reveal the small measure of light, hope, and meaning that Markov was still able to find during his all-too-short life.

R.I.P….

… and yes, the world will not forget your photographs. Well, I certainly won’t!

No Comments