On my Bookshelf | Nikita Teryoshin – Nothing Personal

On my Bookshelf

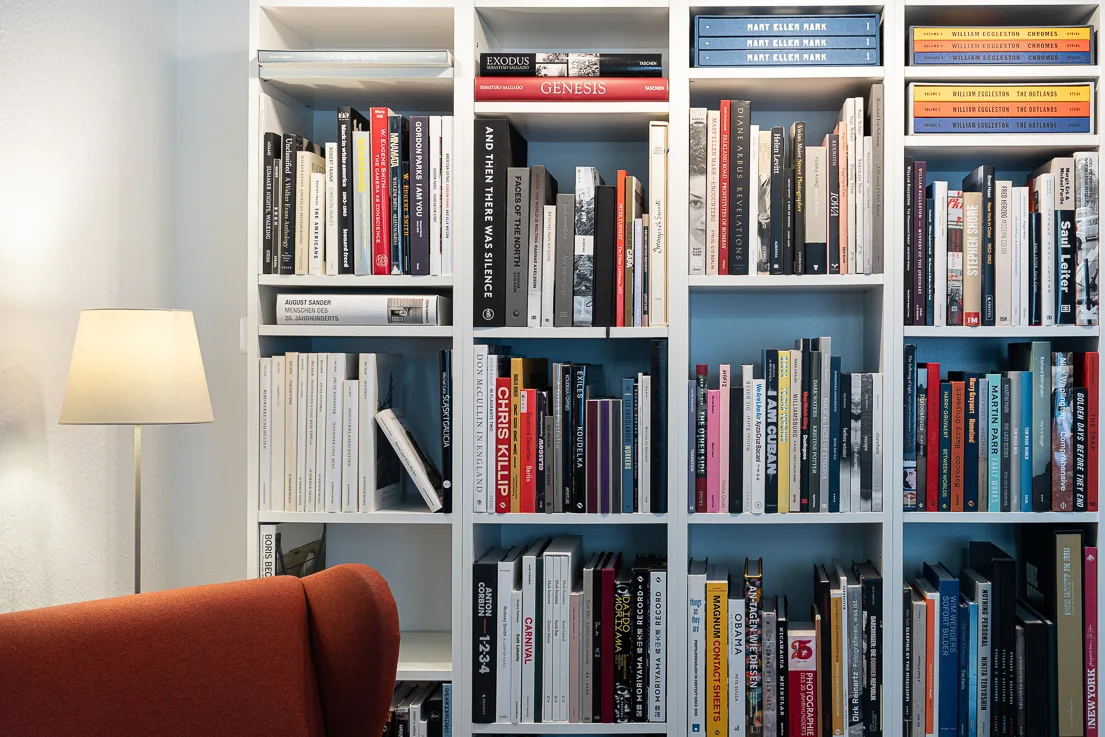

In this column, I occasionally present a photo book that is close to my heart. It is not – or not necessarily – a new publication. It is simply a book that somehow fell into my hands and that I would like to recommend to others. And yes – of course it’s on my bookshelf.

It’s a bit of a continuation of my Photo book of the month column – just not necessarily as regular as before. And I’ve generally made the column a bit shorter and tighter. I hope you’ll enjoy it!

Prologue

In January 2026, I finally chose a book that had been on my shortlist for my personal Book of the Year 2025 for quite some time: Nothing Personal by Nikita Teryoshin. The reason it didn’t ultimately make the cut—while another book did—was, as briefly mentioned there, due to very personal developments. But part of it was also because this book plunged me into a minor emotional conflict. Not because of the photography—certainly not—but because of what the images depict. In times like these, it isn’t always easy to engage with such content. At least not for me. When I present the book below, you’ll probably understand what I mean.

In the end, I chose it as my Book of the Month for January 2026 for a simple reason: despite everything, it’s a great book—one that, sadly, feels more relevant than ever.

About the Photographer | Nikita Teryoshin

Nikita Teryoshin is a German photographer with Russian—or historically more precise, Soviet—roots. He was born in Leningrad (today St. Petersburg), in what was then the USSR, in 1986. At the age of 13, his family moved to Dortmund, Germany, where he went to school and later completed a Bachelor of Arts degree in photography.

Influenced by his father, who worked as a painter and set designer for theatre and television, Teryoshin has long gravitated toward what happens behind the scenes. He takes a particular interest in backstages, where small, often overlooked stories quietly mirror broader social and political realities.

Even during his studies, Teryoshin developed a strong passion for documentary photography. He tended to look where few others bothered to look closely—even when the subject itself was large and seemingly obvious. His final thesis project, Hornless Heritage, for example, explores the sometimes bizarre and absurd lives and impact of today’s high-performance dairy cows. You can already clearly see Teryoshin’s style in this early work: clear, direct, bold, and colourful, but always layered with subtle humour and irony, occasionally edging into cynicism.

Since then, Nikita Teryoshin has held numerous exhibitions, produced several smaller book projects on his own, and received many awards for his work. He works both freelance and on commission for well-known newspapers and magazines and lives in Berlin.

About the Photo Book | Nothing Personal

The project

For the project Nothing Personal, with the telling subtitle The Back Office of War, Nikita Teryoshin visited between 2016 and 2024 around 20 arms fairs in 17 countries across five continents. Accredited as a photojournalist, he was able to gain first-hand insight into these trade fairs, which are closed to the general public. According to him, this interest began at another trade fair, the German event Jagd & Hund (Hunting & Dogs), which, as the name suggests, is devoted to hunting. There, Teryoshin was both astonished and fascinated by people’s enthusiasm for guns, especially among fathers and sons.

The Book

This project later culminated in the publication of Nothing Personal – The Back Office of War in 2024, marking his first major monograph. Published by GOST, the book spans 182 pages and features 100 photographs from the project. It is elegantly bound in linen and carries no title on the front cover, instead displaying a printed image from the series. The book concludes with an explanatory essay by Linda Åkerström.

When you first flip through the book, it feels like Teryoshin has organized the photos into chapters. But those “chapters” are actually slogans from the industry that he picked up at the trade fairs. The images themselves don’t seem to follow a clear chronological or thematic order. However, he’s deliberately paired each slogan with an image on the facing page that reflects its meaning very well.

Just allow yourselves to take in the pictures with the same blend of amazement and irritation I felt. Be prepared for a whole spectrum of emotions, from laughter to disgust—sometimes both at once. And take your time to look closely at the pictures. It’s often the small details that make the picture.

Why do I recommend this book?

A surreal world

First of all, there is one very obvious reason. Nikita Teryoshin’s project—and now his book—takes us into a special world that is completely unknown to most people. Even for me, despite having some professional involvement in aspects of the security and defence sector, the world of arms fairs is entirely foreign. And it turns out to be even more bizarre than one might imagine.

A world as glittering and colourful as a blend of Disneyland and Las Vegas. A world in which champagne and canapés are served among combat helicopters, ammunition and machine guns. For outsiders like me, it can really only be described with three words: amused, speechless, and disgusted.

The human factor

But at the end of the day, it’s really the people who matter most in this world. People don’t just produce these weapons—which are then, sadly, used again and again. But that’s not what this is about. It’s about the people who trade in them, of course, and who are clearly doing more than just good business in this industry.

But Nikita Teryoshin doesn’t show these people as journalistic profiles or named individuals—some of whom might even be well known. Instead, he presents them as anonymous players in this game, which isn’t actually funny at all, but sadly very real. In some photos, that anonymity even turns into a stylistic device, almost like a running gag, with the faces of trade fair visitors repeatedly and seemingly at random covered up. We don’t know who they are, and everyone is free to form their own opinion about who these people might be.

Teryoshin himself has said that he deliberately didn’t want to personalize these people, but instead show them as anonymous parts of a system—and by doing that, show the system itself. And sure, I believe him. Still, I can’t help thinking that legal reasons probably played a pretty big role in that decision too, at the very least.

The Photography

Despite the seriousness of the subject—and all the madness of that world—Teryoshin’s pictures are still striking overall. They have a style all their own, quite distinctive, and perhaps only loosely comparable to Martin Parr’s work. He shows us this world as he experiences it: colorful, somewhat glamorous, and deeply strange. His photography is direct, with heavy use of flash and bold, stark compositions. And even though the style is wild and often very funny, the images also feel carefully chosen, with real depth and, in the truest sense of the word, a strong sense of multidimensionality.

He is particularly skilled at playing with details and storytelling, often placing the foreground or background in a sometimes bizarre relationship to the main subject. And although the images can feel quick and brutally direct, they truly reward a slower, closer look. Every time I’ve flipped through the book again, I’ve noticed new details and layers in the pictures—and I’m sure there is still more to discover.

So what’s the takeaway from all this?

I am left with a slightly unsettled feeling. Not because of the book, which is truly excellent. Nor, from what I can gather from interviews and public appearances, because of Nikita Teryoshin himself. He seems to be a very thoughtful, intelligent, funny, and kind person. And not even because of the weapons themselves. In a world that is not always run by good people, military defense unfortunately also has its place. That is why I do not fundamentally condemn the arms industry.

What troubles me is the way this industry deals with a commodity that is anything but commonplace and far from risk-free. As presented in this book, it once again seems highly questionable—if not outright cynical and, in some cases, perverse. Of course, this is a photographic work, and photographs inevitably reflect, at least to some degree, the photographer’s judgment. But what is shown is also real and mirrors what we all otherwise notice in this regard. In that sense, Nothing Personal is also a political book—one that should make one think. Today, this is more important than ever.

Dear Peter. A great comment on this book. I also like Nikita’s works and especially these, which I was also allowed to see as an exhibition at Freelens in Hamburg. Great! And thank you for your great article.

Best Florian

Hi Florian,

Well, you’re quick today! Nice to see that we have the same taste again. And in this case, too, you’re ahead of me with the exhibition, which I unfortunately never saw. I think it’s definitely worth seeing…

Best regards

Peter

It is a great book.

I am sure you’d like this behind the scenes video from one of the arms fairs (in Paris, I think): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RKN5sFgC8J4

Very interesting to see him work!

Cool… I didn’t know that, thank you!